The Art & State of Safety Journal Club, 05/05/21

Excerpts from “Engaging senior management to improve the safety culture of a chemical development organization thru the SPYDR (Safety as Part of Your Daily Routine) lab visit program”

written by Victor Rosso, Jeffery Simon, Matthew Hickey, Christina Risatti, Chris Sfouggatakis, Lydia Breckenridge, Sha Lou, Robert Forest, Grace Chiou, Jonathan Marshall, and Jean Tom

Presented by Victor Rosso

Bristol-Myers Squibb

The full paper can be found here: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1016/j.jchas.2019.03.005

INTRODUCTION

The improvement and enrichment of an organization’s safety culture are common goals throughout both industrial and academic research. As a chemical process development organization that designs and develops safe, efficient, environmentally appropriate and economically viable chemical processes for the manufacture of small molecule drug substances, we continually strive to improve our safety culture. Cultivating and energizing a rich safety culture is critical for an organization whose members are performing a multitude of processes at different scales using a broad spectrum of hazardous chemical reagents as its core activities. While we certainly place an emphasis on utilizing greener materials and safer reagents, the nature of our business requires us to work with all types of hazardous and reactive chemicals and the challenges we face are pertinent to any chemical research organization.

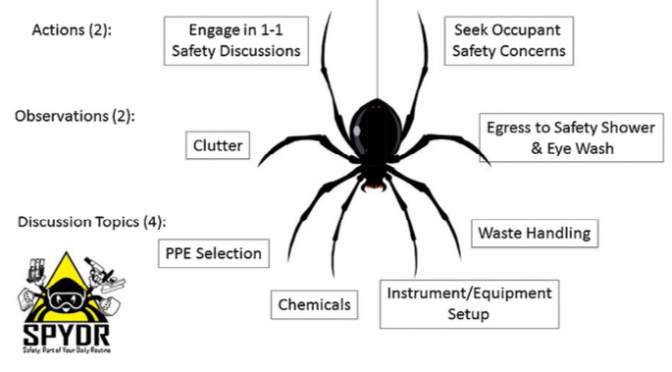

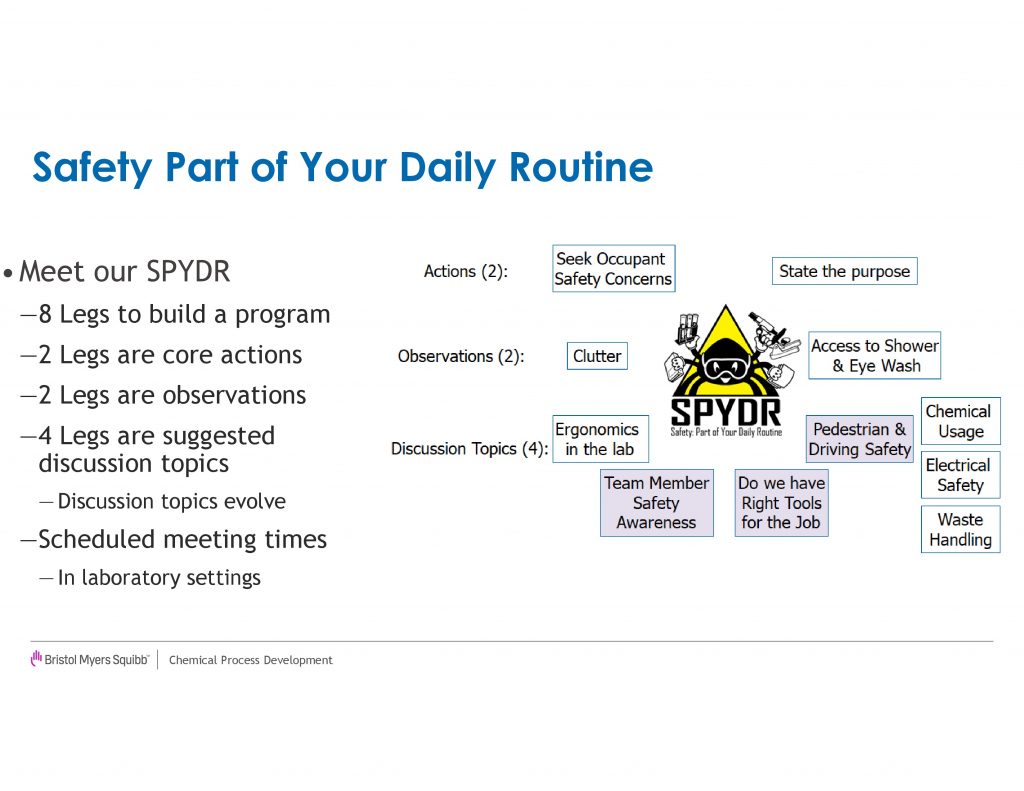

In our organization of approximately 200 organic and analytical chemists[a] and chemical engineers, we have a Safety Culture Team (SCT) [b][c][d][e][f][g]whose mission is to develop programs to enhance the organization’s safety culture. To make this culture visible, the team developed a key concept, Safety is Part of Your Daily Routine, into a brand with its own logo SPYDR. To build on this concept, we designed a program known as the SPYDR Lab Visits shown in Figure 1. The program engages our senior leadership[h][i] by having them interact with our scientists directly at the bench in the laboratory[j][k][l][m] to discuss safety concerns. This program, initiated in 2013, has visibly engaged our senior leaders directly in the organization’s safety culture and brought to our attention a wide range of safety concerns that would not readily appear[n][o][p] in a typical safety inspection. Furthermore, this program provides a mechanism for increased communication between all levels of the organization by arranging meetings between personnel who may not normally interact with one another on a regular basis. The success of this program has led to similar programs across other functional areas in the company.[q]

A key safety objective for all organizations is to ensure that the entire organization can trust that the leadership is engaged in and supportive of the safety culture. [r][s][t][u]Therefore this program was designed to (1) emphasize that safety is a top priority from the top of the organization to the bottom[v][w][x][y][z], (2) engage our senior leadership with a prominent role in the safety conversations in the organization, (3) build a closer relationship between our senior leaders and the laboratory occupants and (4) utilize the feedback obtained from the visits to make the working environment better for our scientists. The program is a supplement to and not a replacement for the long standing laboratory inspection program done by the scientists in the organization.

The program involves assigning the senior leaders to meet with 2–5 scientists in the scientists’ laboratory. There are approximately 40 laboratories in the organization, and over the course of the year, each laboratory will meet with 2–3 senior leaders and each senior leader will visit 4–6 different laboratories. All of this is organized using calendar entries which informs the senior leaders and scientists of where and when to meet, and contains the survey link to collect the feedback.

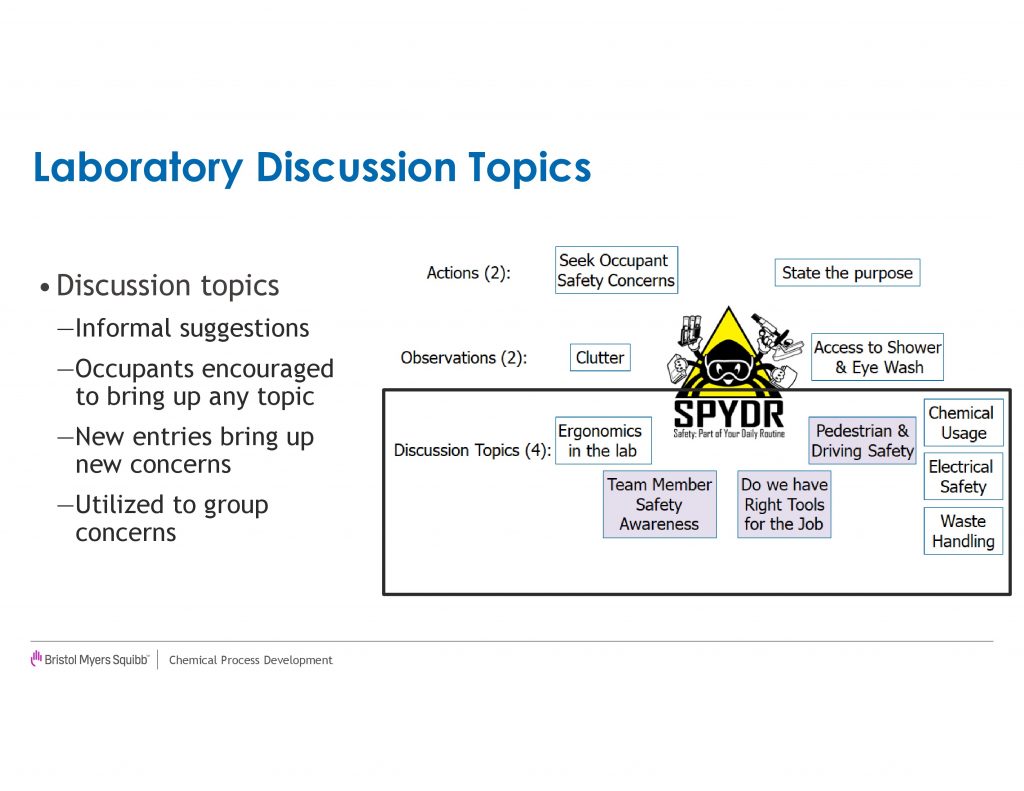

As a result of this program, our senior leaders engage our bench scientists in conversations that are primarily driven to draw out the safety concerns of our scientists. However, these conversations can run the gamut of anything that is a concern to our team members[aa][ab]. This can range from safety issues, laboratory operations, and current research work to organizational changes and personal concerns. The senior leadership regularly reminds and encourages the scientists to engage on any topic of their choosing; this creates a collegial atmosphere for laboratory occupants to voice their safety concerns and ideas.

The laboratory visit program was modeled around the Safety SPYDR and thus we designed the program to have 8 legs[ac]. The first two legs consist of the program’s goals for the visit. We asked the senior leaders to ensure that they state the purpose of the program, that they are visiting the laboratory to find ways to improve lab safety. The second leg, which is the primary goal, is to ask “what are your safety concerns?”. Often this is met with “we have no safety concerns”, but using techniques common in the interviewing process, the leaders ask deeper probing questions to draw out what the scientists care about and with additional probing[ad][ae][af][ag], root causes of the safety concerns will emerge. Once the scientists start talking about one safety concern, often multiple concerns will then surface, thus giving our safety teams an opportunity to deal with these concerns.

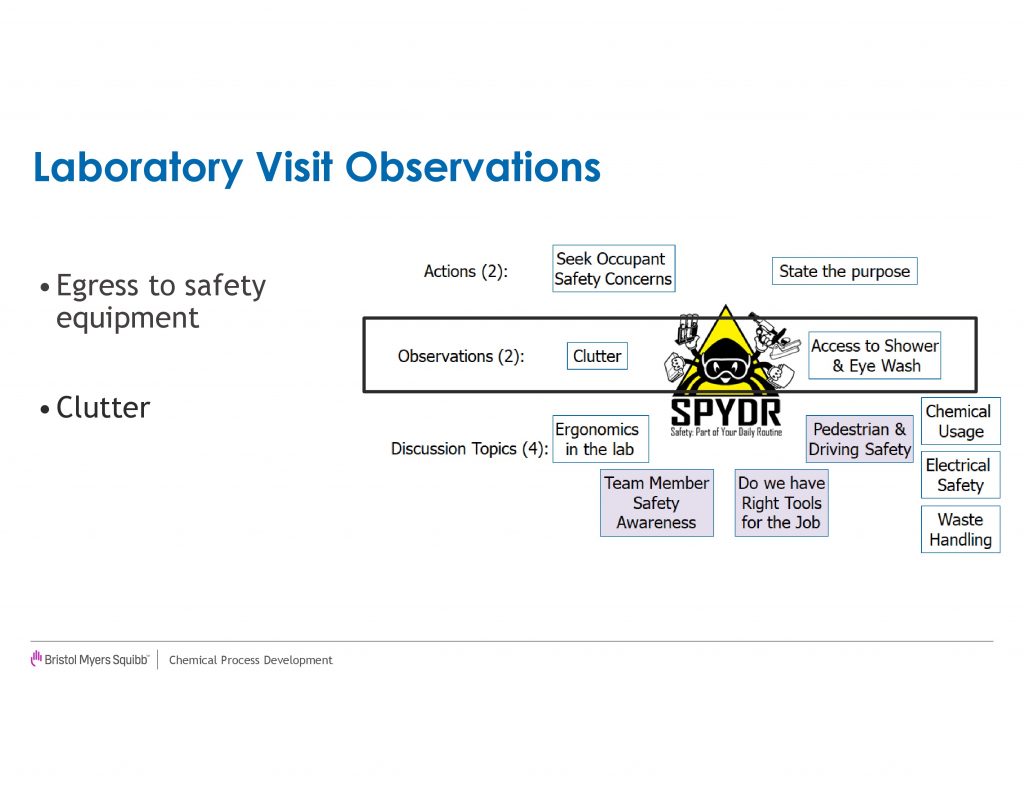

The next two legs of the SPYDR Lab visits consist of observations we ask our senior leaders to make on laboratory clutter and access to emergency equipment[ah]. If the clutter level of a laboratory is deemed unacceptable,[ai][aj][ak][al] the SCT will look to provide support to address root causes of the clutter. Typical solutions have been addition of storage capacity, removal of excess equipment from the work spaces, and alternative workflows. The second observation is to ensure clear paths from the work areas to emergency equipment exist, should an incident occur. We wanted to make sure a direct line existed to the eyewash station/shower such that the occupant would not be tripping over excessive carts, chillers, shelving or miscellaneous equipment. These observations led to active coaching of our laboratory occupants to ensure safe egress existed and modifications to the work environment. For example, the relocation of many chillers to compartments underneath the hood from being on a cart in front of the hood enabled improved egress for a number of laboratories.

For the final four legs of the SPYDR Visit, we ask the senior leaders to probe for understanding on various topics[am] that range from personal protective equipment selection, waste handling, reactor setup and chemical hazards. The visitor is asked to rate these areas from needs improvements, to average, high, or very high. Figure 2 compares these ratings from the first year (2013) with the current year (2018). In the first year of the program, there were a few scattered “needs improvement” rating that resulted in communication with the line management of the laboratory. After the initial year, “needs improvement” ratings became very rare in all cases except clutter. In the current year, we shifted two topics[an] to Laboratory Ergonomics[ao] and Electricity, which uncovered additional opportunities for improvement. We recommend changing the contents of these legs on a regular basis[ap] as it shifts the focus of the discussion and potentially uncovers new safety concerns.

FEEDBACK MECHANISM

The SPYDR lab visits are built around a feedback loop illustrated in Figure 3 that utilizes an online survey to both track completion of the visits as well as to communicate findings back to the SCT. The order of events around a laboratory visit consist of scheduling a half hour meeting between our senior leaders and the occupants in their laboratories. Once the visit is completed, the visitors will fill out the simple online survey (Figure 4) that details their findings for the visit. The SCT will meet regularly to review the surveys and take actions based on the occupants’ safety concerns. This often involves following up with the team members in the laboratory to ensure they know their safety concerns were heard[aq][ar].

Two potential and significant detractors for this program exist. The first challenge is if the senior visitor does not show up for the visit, this results in a perception that senior management does not embrace safety as a top priority. The second pitfall is if the visitor uncovers a safety concern, but does not fill out the survey to report safety concerns, or if the SCT is unable to address a safety concern. In this case, there would be a perception that a safety concern was reported to a senior leader and “nothing happened”. To minimize these risks, there is significant emphasis for the senior leaders to take ownership of the laboratory visits[as][at] and for the SCT to take ownership of the action items and ensure the team members know their voices have been heard.

DISCUSSION OF SAFETY CONCERNS

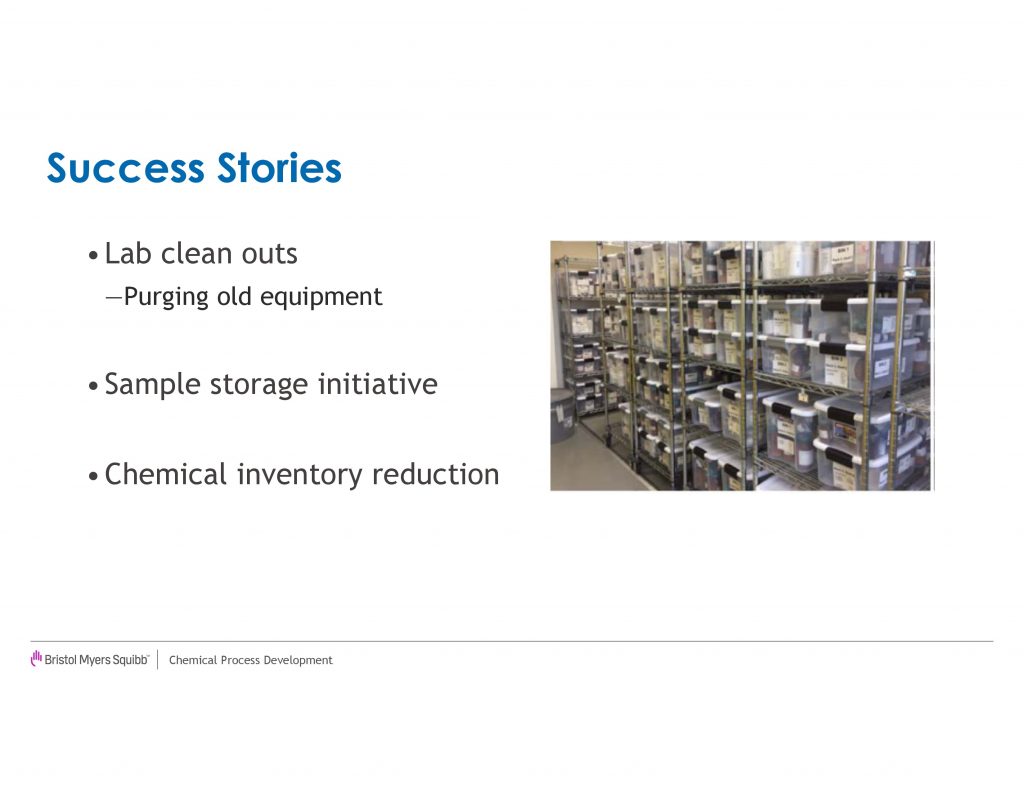

A summary of safety concerns is illustrated in Table 1. By a wide margin, clutter was the predominant safety concern in 2013 as it was noted in 50% of the laboratories visited. Three major safety programs within the department were inspired by early visits in order to reduce clutter in the laboratories. This included several rounds of organized general laboratory cleanouts to remove old equipment[au][av]. A second program systematically purged old and/or duplicate chemicals throughout the department.[aw] Most recently, a third program created a systematic long term chemical inventory management system[ax][ay][az] that was designed to reduce clutter caused by the large number of processing samples stored in the department. This program has returned over 900 sq. feet of storage space to our laboratories and has greatly reduced the amount of clutter in the labs. Although clutter remains a common theme in our visits, the focus is now often related to removal of old instruments and equipment [ba][bb][bc][bd]rather than a gross shortage of storage space.

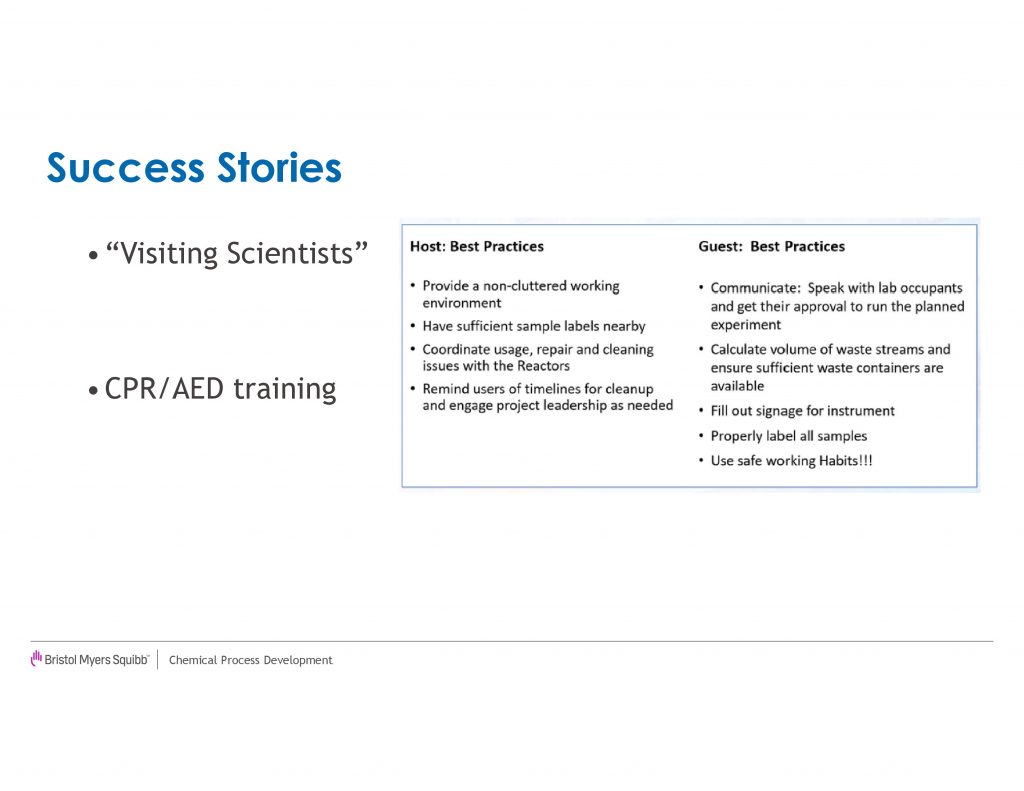

In the first year of the program, one aspect of the laboratory visit was to discuss hazards associated with chemical reactions (feedback rate of 28%) and equipment setup (32%). A common thread in these discussions were expectations of collaboration and behavior from “visiting scientists”. These “visiting scientists” were colleagues[be][bf][bg][bh] and project team members from other laboratories coming to the specific laboratory in order to use its specialized equipment (examples: 20 liter reactors, automated reactor blocks). This caused certain friction between the visiting scientists and their hosts on safety expectations. The SCT addressed this by convening a meeting between hosts and visiting scientists to discuss root causes of friction to produce a list of “best practices” shown in Figure 5 to improve the work experience for both hosts and visitors that is still in use for specialty labs with shared equipment today.[bi][bj]

The next major category of safety concerns for our laboratory visits was associated with facility repairs which was present in 24% of our first year visits. These included items such as leaking roofs, unsafe cabinet doors, or delays in re-energizing hoods after fire drills. These were addressed by connecting our scientists to the appropriate building managers who would be able to evaluate and address these safety concerns. After the initial year, most of the facility related concerns transitioned to the addition/removal of storage solutions within specific laboratories. Currently, when new laboratories are associated with the SPYDR Lab Visit program, major facility concerns will quickly be reported.

These visits also brought to light a common problem occurring in the laboratories, that is, the loss of electrical power associated with circuit breakers being tripped when the electrical outlets associated with a laboratory hood were being used at capacity. This led to the identification of the need to increase the electrical capacity in the fume hoods and this Is now being addressed by an ongoing capital project.

By the third year of the program, the nature of the safety concerns changed as many of the laboratory-based concerns had been addressed[bk]. Concerns raised now included site issues such as traffic patterns, pedestrian safety, walking in parking lots at night, and training. [bl]Among the items addressed for the site include on-site intersections being modified and movement of a fence line to enable safer crosswalks and improvements for the driver’s line-of-sight. A simple question raised about fire extinguisher training and who was permitted to use an AED device led to the expansion of departmental fire extinguisher training to a broader group and the offering of AED/CPR training to the broader organization.

These safety concerns would not be typically detected by a laboratory safety inspection program and are only accessible by directly asking the occupants what their safety concerns are. [bm][bn][bo]Through the SCT, these issues were resolved over time as the team took accountability to move the issue through various channels (facilities, capital projects, ordering of equipment) to develop and implement the solutions.

CONCLUSION

Since 2013, this novel program[bp] has successfully engaged our leadership with laboratory personnel and has led to hundreds of concerns being addressed[bq]. The concerns have arisen from over 300 laboratory visits, and more than a thousand safety conversations with our scientists. Because this is not a safety inspection program, these visits routinely uncover new safety concerns that would not be expected to surface in our typical laboratory inspection program. The SPYDR visit program is a strong supplement to the laboratory inspection program, and has produced a measurable impact on the safety culture.

A collateral benefit from the program is that it drives social interactions within the department where senior leaders who may not necessarily interact with certain parts of the organization have a chance to visit these team members in their workplace and learn firsthand what they do in the organization[br][bs][bt][bu].

[a]Only a bit bigger than some of the bigger graduate chemistry programs in the US.

[b]How large is the Safety culture Team?

[c]in the range of 6-10

[d]Does this fall in the “other duties as assigned” category or more driven by personal interest in the topic?

[e]Do position descriptions during recruitment include Required or Preferred skills that would add value to inclusion on the SCT?

[f]I was unable to access the article in its entirety so this question may be answered there…. What is the composition of the SCT- who in the organization participates?

[g]representatives from various departments and leaders of safety teams

[h]do some of the senior leadership going to the labs have lab experience?

[i]yes

[j]Was this a formal thing or out of the blue visits?

[k]initially planned as random, unannounced, we had to revert to scheduled in order to ensure scientists were present and available when leaders stopped in

[l]We had the same thing in academic lab inspections. While unannounced visits seemed more intuitive, the benefit of the visits wasn’t there if the lab workers weren’t available to work with the inspectors. So scheduling visits worked out better in the end

[m]In terms of compliance inspections, I would think that the benefit of scheduled inspections is that it can motivate people to clean their labs before the inspection. While I get that it would be preferable that they clean their labs more regularly, the announced visit seems like it would guarantee that all labs get cleaned up at least once per year. And maybe they’ll see the benefit of the cleaner lab and be more inspired to keep it cleaner generally – but I realize that might just be wishful thinking.

[n]So important. We keep running into the issues of experimental safety getting missed by 1-shot inspections.

[o]Some of that could be addressed with better risk assessment training of research staff.

[p]concerns are generally wide ranging, most started out as lab centric in the early years then expanded beyond the labs

[q]Are these other functional areas related to safety or other issues (e.g. quality control, business processes, etc.)

[r]This seems key but also can be super hard to obtain.

[s]I think that it requires leadership that is familiar with all of the different kinds of expertise in the orgainzation to say that. Higher ed contains so many different types of expertise, it is difficult for leadership to know what this commitment entails

[t]And far too often in my experience in academia those in leadership positions have limited management training, which can inhibit good leadership traits.

[u]Many academics promoted into chair or dean level get stuck on budgeting arguments rather than more strategic / visionary questions

[v]I’ve found this expectation to be quite challenging at some higher ed institutions.

[w]Everytime I bring it up to upper management in higher ed, they say “of course safety is #1”, but they don’t want to spend their leadership capital on it.

[x]the program was designed to give senior leaders a role specifically designed for them

[y]@Ralph I completely agree!

[z]This approach seems to be a way for leadership to get involved with out spending a lot of leadership capital.

I always had my best luck “inspecting” labs when I could lead with science-related questions rather than compliance issues

[aa]I think it is really cool that this is thought of expansively.

[ab]Nice to not put bounds on safety concerns going into the conversation. Reinforced later in the paper thru the identification and mitigation of hazards well outside the lab

[ac]Are these legs connected to on boarding training for lab employees?

[ad]This skill would be exceptionally important when discussing such issues with graduate students.

[ae]Are scientists trained in this technique? Or does the SCT have individuals selected for that skill set? When I look around campus at TTU I can see lots of opportunity for collaboration by bringing “non-scientists” into the discussion to get new perspectives and possibly see new problems

[af]This definitely takes practice, but it can also be learned in workshops and by observing good mentoring. The observation process requires a conscious commitment by both the mentor and the employee, though

[ag]one thought at least for me, was the interviewing experience senior folks would have and this would be a chance to practice said skill

[ah]Seems like the process could have some standard topics that can be replaced with new focus areas as the program matures or issues are addressed

[ai]Lab clutter is an ongoing stress for me. Is the clutter related to current work or a legacy of previous work that hasn’t been officially decommissioned yet?

Did your organization develop a set of process decommissioning criteria to maintain lab housekeeping?

[aj]Part of me feels that all researchers should at some point visit/tour a trace analytical laboratory. Contamination is always of such concern when looking for things at ppb/ppt/ppq levels, that clutter rarely develops. But outside of trace analysis laboratory its definitely a continuous problem in most research spaces.

[ak]This is a good idea. I wonder if Bristol Myers Squibb has a program to rotate scientists among different lab groups to share “cross-cultural” learning?

[al]@Chris – good point. I started research in a molecular genetics lab. While there were some issues, the benches and hoods were definitely MUCH cleaner and better organized because of concerns over contamination. Also, we have lab colonies of different insects in which things had to be kept very clean in order to keep lab-acquired disease transmission low for the insects. I was FLOORED by what I saw in chemistry labs once I joined my department. We very much had different ideas about what “clean” meant.

[am]I really like this idea as well. Make sure everyone is on the same page.

[an]I like the idea of shifting focus the previous issues have been addressed

[ao]Great to see emphasis on an often overlooked topic

[ap]Would reviewing these legs annually be regular enough? Or too often?

[aq]So important – people are more willing to discuss issues if they feel like someone is really listening and is prepared to actually address the issues.

[ar]And it demonstrates true commitment to the program and improvements. Supports the trust built between the different stakeholders.

[as]Is there some sort of training or prepping down with these senior leaders?

[at]a short training session occurs to introduce leaders to the purpose of the program

[au]Thank you! This is a challenge for all laboratory organizations I have worked for

[av]Agreed! Too often things are kept even when there is no definitive plan for future use.

[aw]What % of the chemical stock did this purge represent?

[ax]I’m always amazed when I learn of a laboratory that attempts to function without a structured chemical management system. The ones without are often those that duplicate chemical purchases, often in quantities of scale (for price savings) that far exceed their consumption need.

[ay]I once asked the chem lab manager about this. He said that 80% of his budget is people and 15% chemicals. He’d rather focus his time on managing the 80% than the 15%.

He had a point, but I think he was passing up an important opportunity with that approach

[az]@Chris – and grad students waste loads of time looking for the reagents and glassware they need for their experiments. And when they find them, sometimes they have been so poorly stored/ignored that they are contaminated or otherwise useless. Welcome to my lab!

[ba]is this more of a challenge in academia vs. industry?

[bb]This is definitely a pretty big issue for us at the university I work at. Constant struggle.

[bc]One of the things I found frustrating while working at a govt lab is that I found out that we legally weren’t allowed to donate old equipment. I was simultaneously attending a tiny PUI nearby who would have LOVED to take the old equipment off their hands. Now working in an academic lab, I have been able to snag some donated equipment from industry labs.

[bd]@Jessica as someone presently in government research I share your frustration! I have to remind myself that the government systems are all too often setup to prevent abuse, rather than be efficient and benevolent.

[be]Are these other laboratories from within your organization or external partners?

[bf]visitors from other labs within the department,

[bg]We had that challenge to some extent, but the bigger issues arose when visitors from other campuses showed up with different safety expectations than we were trying to instill. International visitors were a particularly interesting challenge…

[bh]@Ralph that was often my experience too, dramatically differing safety expectations now being asked to share research space.

[bi]I wish this occurred with greater frequency in academia. Too often folks are too concerned about hurting a colleagues’ feelings or ego than to have a conversation to address safety concerns.

[bj]I like the best practices approach- less prescriptive and allows researchers some latitude in meeting the requirements. Provides an opportunity for someone (who is a subject matter expert in their field) to come up with a better solution

[bk]That’s great, shows a commitment to the program and supports the trust that has been built between the stakeholders.

[bl]These are important issues in setting the tone of a safety culture for an organization

[bm]Such an important statement here.

[bn]Agreed!

[bo]+1

[bp]This is a good one!

[bq]Since I’m sure these were tracked, this is a nice metric- prevalence of a particular concern over time.

[br]does this go both ways at all? do the research scientists have the chance to ask how their research projects impact the goals of senior leadership/company?

[bs]there is a social interaction aspect here were scientists will get to interact with leaders they normally would not cross paths with, we can take this opportunity for our analytical leaders to visit chemists, chemistry leaders to visit engineers and engineering leads to visit analytical chemists

[bt]Did business leadership (sales, marketing, etc.) have the opportunity to see this kind of interaction? Or do they have separate interactions with lab staff?

[bu]In higher ed, it would be interesting to take admissions staff on lab tours to inform them about what is going on there and potentially give feedback about what students and parents are interested in