Category Archives: safety culture

Resources for Improving Safety Culture, Training, and Awareness in the Academic Laboratory

Dr. Quinton J. Bruch, April 7th, 2022

Excerpts from “Resources for Improving Safety Culture, Training, and Awareness in the Academic Laboratory”

Full paper can be found here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780081026885000921?via%3Dihub

Full paper can be found here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780081026885000921?via%3Dihub

Theme 1: Setting Core Values and Leading By Example.

Mission statements. …Mission statements establish the priorities and values of an organization, and can be useful in setting a positive example and signaling to potential new researchers the importance of safety. To examine the current state of public-facing mission statements, we accessed the websites of the top [a][b]50 chemistry graduate programs in the United States and searched any published mission statements for mentions of safety. [c]Although 29 departments had prominently displayed mission statements on their websites, only two (the University of Pennsylvania and UMN) included practicing safe chemistry in their mission statement (~at time of publishing in early 2021).[d][e][f][g]

Regular and consistent discussions about safety. Leaders can demonstrate that safety is a priority by regularly discussing safety in the context of experimental set-up, research presentations, literature presentations, or other student interactions[h][i]. Many potential safety teaching moments occur during routine discussions of the day-to-day lab experience.[j] Additionally, “safety minutes[k][l]”[m][n] have become a popular method in both industry and academia to address safety at the beginning of meetings.

Holding researchers accountable[o][p]. In an academic setting, researchers are still in the trainee stage of the career. As a result, it is important to hold follow-up discussions on safety to ensure that they are being properly implemented.[q] For example, in the UMN Department of Chemistry a subset of the departmental safety committee performs regular PPE “spot checks,”[r][s] and highlights exemplary behavior through spotlights in departmental media. Additionally, each UMN chemistry graduate student participates in an annual review process that includes laboratory safety as a formal category.[t] Candid discussion and follow-up on safe practices is critical for effective trainee development.

Theme 2: Empowering Researchers to Collaborate and Practice Safe Science.

Within a group: designate safety officers. Empower group members to take charge of safety within a group, both as individuals and through formal appointed roles such as laboratory safety officers (LSOs).[u] LSOs can serve multiple important roles within a research group. First, LSOs can act as a safety role model for peers in the research group, and also as a resource for departmental policy. Further, they act as liaisons to ensure open communication between the PI, the research group, and EHS staff. These types of formal liaisons are critical for fostering collaborations between a PI, EHS, and the researchers actually carrying out labwork. LSOs can also assist [v][w]with routine safety upkeep in a lab, such as managing hazardous waste removal protocols and regularly testing safety equipment such as eyewash stations. For example, in the departments of chemistry at UMN and UNC, LSOs are responsible for periodically flushing eyewash stations and recording the check on nearby signage[x].[y][z][aa][ab] Finally, LSOs are also natural picks for department-level initiatives such as department safety committees or student-led joint safety teams.[ac]

Within a group: work on policies as a collective. Have researchers co-write, edit, and revise standard operating procedures (SOPs).[ad] Many EHS offices have guides and templates for writing SOPs. More details on SOPs will be discussed in the training section of this chapter. Co-writing has the double benefit of acting as a safety teaching moment while also helping researchers feel more engaged and responsible for the safety protocols of the group.[ae][af][ag]

Within a department: establish safety collaborations.[ah] Research groups within departments often have very diverse sets of expertise. These should be leveraged through collaboration to complement “blind spots”[ai] within a particular group to the benefit of all involved—commonly, this is done through departmental safety committees, but alternative (or complementary) models are emerging. An extremely successful and increasingly popular strategy for establishing department-wide safety collaborations is the Joint Safety Team model.

Joint Safety Teams (JSTs). A Joint Safety Team (JST) is a collaborative, graduate student- and postdoc-led initiative with the goal of proliferating a culture of laboratory safety by bridging the gaps between safety administration, departmental administration, and researchers. JSTs are built on the premise that grassroots efforts can empower students to take ownership of safety practices, thus improving safety culture from the ground up. Since its inception in 2012, the first JST at UMN (a joint endeavor between the departments of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering & Materials Science, spurred through collaboration with Dow Chemical) has directly and significantly impacted the adoption of improved safety practices, and also noticeably improved the overall safety culture. Indeed, the energy and enthusiasm of students, which are well-recognized as key drivers in research innovation, can also be a significant driver for improving safety culture.[aj][ak]

…The JST model has several advantages[al]: (1) it spreads the safety burden across a greater number of stakeholders, reducing the workload for any one individual or committee; (2) it provides departmental leadership with better insight into the “on-the-ground” attitudes and behaviors of researchers;[am][an][ao][ap] and (3) it provides students with practical safety leadership opportunities that will be beneficial to their career. In fact, many of the strategies discussed in this chapter can be either traced back to a JST, or could potentially be implemented by a JST.

An inherent challenge with student-led initiatives like JSTs is that the high student turnover in a graduate program necessitates ongoing enthusiastic participation of students after the first generation. In fact, after the first generation of LSOs left the UMN JST upon graduation, there was a temporary lag in enthusiasm and engagement. In order to maintain consistent engagement with the JST, the departmental administration created small salary bonuses for officer-level positions within the JST, as well as a funded TA position. Since spending time on JST activities takes away from potential research or other time, it seems reasonable that students be compensated accordingly when resources allow it…[aq][ar]

3. Training

Initial Safety Training. Chemical safety training often starts with standardized, institution-wide modules that accompany a comprehensive chemical hygiene plan or laboratory safety manual. These are important resources, but researchers can be overwhelmed by the amount of information[as][at]—particularly if only some components seem directly relevant. There is anecdotal evidence that augmentation with departmental-level training[au][av][aw] initiatives can provide a stronger safety training foundation. For example, several departments have implemented laboratory safety courses. At UNC, a course for all first-year chemistry graduate students was created with the goal of providing additional training tailored to the department’s students. Iteratively refined using student feedback, the course operates via a “flipped classroom” model to maximize engagement. The course combines case study-based instruction, role playing (i.e., “what would you do” scenarios), hands-on activities (e.g., field trips to academic labs), and discussions led by active researchers in chemistry subdisciplines or industrial research.

Continued Safety Training[ax]. Maintaining engagement and critical thinking about safety can help assure that individual researchers continue to use safe practices,[ay] and can strengthen the broader safety culture. Without reinforcement, complacency is to be expected—and this can lead to catastrophe. We believe continued training can go well beyond an annual review of documentation by incorporating aspects of safety training seamlessly into existing frameworks.

Departments can incorporate safety minutes into weekly seminars or meetings, creating dedicated time for safety discussions (e.g., specific hazards, risk assessment, or emergency action plans). In our experience, safety minutes are most effective when they combine interactive prompts[az] that encourage researcher participation and discussion. These safety minutes allow researchers to learn from one another and collaborate on safety.

While safety minutes provide continuous exposure and opportunities to practice thinking about safety, they lack critical hands-on (re)learning experiences. Some institutions have implemented annual researcher-driven activities to help address this challenge. For example, researchers at UNC started “safety field days” (harkening back to field days in grade school) designed specifically to offer practice with hands-on techniques in small groups. At UMN, principal investigators participate in an annual SOP “peer review” process, in which two PIs pair up and discuss strengths and potential weaknesses of a given research group’s SOP portfolio.[ba][bb]

Continued training can also come, perhaps paradoxically, when a researcher steps into a mentoring role to train someone else. The act of mentoring a less experienced researcher provides training to the mentee, but also forces the mentor to re-establish a commitment to safe practices and re-learn best practices[bc].[bd] Peer teaching approaches have long been known to improve learning outcomes for both the mentor and the mentee. With regards to safety training, mentors would be re-exposed to a number of resources used in initial safety trainings, such as SOPs, while having to demonstrate mastery over the material through their teaching. Furthermore, providing hands-on instruction would require demonstrating techniques for mentees and subsequently critically assessing and correcting the mentee’s technique. Additionally, mentors would have to engage in critical thinking about safety while answering questions and guiding the mentee’s risk assessments.

Continued training is important for all members of a research group. Seniority does not necessarily convey innate understandings of safety, nor does it exempt oneself from complacency. For example, incoming postdocs[be] will bring a wealth of research and safety knowledge, but they may not be as intimately familiar with all of the hazards or procedures of their new lab, or they may come from a group or department with a different safety culture. Discussing safety with researchers can be difficult, but is a necessary part of both initial and continued training.

4. Awareness[bf]

Awareness as it pertains to chemical safety involves building layers of experience and expertise on top of safety training. It is about being mindful and engaged in the lab and being proactive and prepared in the event of an adverse scenario. Awareness is about foreseeing and avoiding accidents before they happen, not just making retroactive changes to prevent them from happening again. There are aspects of awareness that come from experiential learning—knowing the sights and sounds of the lab—while other aspects grow out of more formal training. For example, awareness of the potential hazards associated with particular materials or procedures likely requires some form of risk assessment.

Heightened awareness grows out of strong training and frequent communication, two facets of an environment with a strong culture of safety. Communication with lab mates, supervisors, EHS staff, industry, and the broader community builds awareness at many levels. Awareness is a critical pillar of laboratory safety because it links the deeply personal aspects of being a laboratory researcher with the broader context of safety communication, training, and culture. It also helps address the challenge of implementing a constructive and supportive infrastructure.

Like any experience-based knowledge, safety awareness will vary significantly between individuals. Members of a group likely have had many of the same experiences, and thus often have overlap in their awareness. Effective mentoring can lead to further overlap by sharing awareness of hazards even when the mentee has not directly experienced the situation. Between groups in a department, however, where the techniques and hazards can vary tremendously, there is often little overlap in safety awareness. [bg][bh][bi][bj]In this section, we consider strategies to heighten researcher safety awareness at various levels through resources and tools that allow for intentional sharing of experiential safety knowledge.

Awareness Within an Academic Laboratory[bk]. …Some level of awareness[bl] will come through formal safety training, as was discussed in the preceding section. Our focus here is on heightened awareness through experiential learning, mindset development, and cultivating communication and teaching to share experience between researchers.

We have encountered or utilized several frameworks for building experience. One widely utilized model involves one-on-one mentoring schemes, where a more experienced researcher is paired with a junior researcher. This provides the junior researcher an opportunity to hear about many experiences and, when working together, the more experienced researcher can point out times when heightened awareness is needed. All the while, the junior researcher is running experiments and learning new techniques. There are drawbacks to this method, though. For example, the mentor may not be as experienced in particular techniques or reagents needed for the junior researcher’s project. Or the mentor may not be effective in sharing experience or teaching awareness. Gaps in senior leadership can develop in a group, leaving mentorship voids or leading to knowledge transfer losses. Like the game “telephone” where one person whispers a message to another in a chain, it is easy for the starting message to change gradually with each transfer of knowledge.[bm] This underscores the importance of effective mentoring,[bn] and providing mentors with a supportive environment and training resources such as SOPs and other documentation…

…Another approach involves discussing a hypothetical scenario, rather than waiting to experience it directly in the lab. Safety scenarios are a type of safety minute that provide an opportunity to proactively consider plausible scenarios that could be encountered.[bo][bp] Whereas many groups or departments discuss how to prevent an accident from happening again, hypothetical scenarios provide a chance to think about how to prevent an accident before it happens[bq][br]. Researchers can mediate these scenarios at group meetings. If a researcher is asked to provide a safety scenario every few weeks, they may also spend more time in the lab thinking about possible situations and how to handle them on their own.

Almost all of these methods constitute some form of risk or hazard assessment. As discussed in the training section, formal risk assessment has not traditionally been part of the academic regimen. Students are often surprised [bs]to learn that they perform informal risk assessments constantly, as they survey a procedure, ask lab mates questions about a reagent, or have a mentor check on an apparatus before proceeding. Intuition provides a valuable risk assessment tool, but only when one’s intuition is strong. A balance[bt] of formal risk assessment and informal, experiential, or intuition-based risk assessment is probably ideal for an academic lab.

…Checklists are another useful tool for checking in on safety awareness. [bu][bv][bw]Checklists are critically important in many fields, including aviation and medicine. They provide a rapid visual cue that can be particularly useful in high-stress situations where rapid recall of proper protocol can be compromised, or in high-repetition situations where forgetting a key step could have negative consequences. Inspired by conversations with EHS staff, the Miller lab recently created checklists that cover daily lab closing, emergency shutdowns, glovebox malfunctions, high-pressure reactor status, vacuum line operations, and more. The checklists are not comprehensive, and do not replace in-person training and SOPs, but instead capture the most important aspects that can cause problems or are commonly forgotten.[bx][by] The signage provides a visual reminder of the experiential learning that each researcher has accumulated, and can provide an aid during a stressful moment when recall can break down.

A unifying theme in these approaches is the development of frameworks for gaining experience with strong mentoring and researcher-centric continued education. Communication is also essential, as this enables the shared experiences of a group to be absorbed by each individual…[bz][ca]

[a]Wondering if these were determined by us news

[b]I can’t remember exactly what we did, but if we were writing this today; that is where I’d probably start. Plenty of discussion about how accurate/useful those rankings are, but in this instance, it serves as a good starting point

[c]If safety is not part of your mission statement or part of the your graduate student handbook, then this could cause issues with any disciplinary actions you may want to take. For instance, we had a graduate student set off the fire alarm twice on purpose in a research intense building. It was difficult for the department this person was part for actions to be taken.

We have a separate section on safety in our handbook “Chemical engineering research often involves handling and disposing of hazardous materials. Graduate

students must follow safe laboratory practices as well as attend a basic safety training seminar before starting

any laboratory work. In order to promote a culture of safety, the department maintains an active Laboratory

Safety Committee composed of the department head, faculty, staff and a student members which meets each

semester. Students are expected to be responsive to the safety improvements suggested by the committee,

to serve on the committee when asked, and utilize the committee members as a resource for lab safety

communication.”

[d]This is an interesting perspective on how others have prioritized safety.

[e]I find these sorts of things ring hollow given how little PIs or department leadership seem to know about what is happening in other people’s labs.

[f]I agree, particularly at the University level. However, a number of labs have mission statements, including the Miller lab, that mentions safety. I think at that level, it certainly can demonstrate greater intent

[g]Agreed. Having that language come from the PI is definitely different from having it come from the department or university – especially if the PI also walks the walk.

[h]So important because what is important to the professor becomes important to the student

[i]I definitely agree with this. I have always noticed that our students immediately reflect, pick up on, and look for what they think their professors deem most necessary/important essential.

[j]I think this is an underappreciated area. These are the conversations that help make safety a part of doing work, not just something bolted on to check a box or provide legal cover.

[k]Is this the same as safety moments?

[l]I would say somewhat? I’ve come to realize that these two terms are often used interchangeable, but can mean very different things. At UNC, what my lab called “safety minutes” would be a dedicated section of group meeting every week where someone would lead a hypothetical scenario or a discussion of how to design a dangerous experiment with cradle-to-grave waste planning. At other places; these can mean things as simple as a static slide before seminar.

[m]The inverse of my comment above. I think these have their place, but if they’re disconnected from what the group’s “really” there to talk about, they can reinforce the idea that safety isn’t a core part of research.

[n]Agreed. I’ve seen some groups implement this by essentially swiping “safety minutes” from someone else. While this could be a way to get started, the items addressed really should be specific to your research group and your lab in order to be meaningful.

[o]Note how all these examples are of the department holding its own researchers accountable, not EHS coming externally to enforce

[p]Yes! It doesn’t fight against the autonomy that’s a core value of academia.

[q]This is a good point. Can’t be a one-and-done although it often feels like it is treated that way.

[r]It seems like this practice would also build awareness and appreciation of the other lab settings and help to foster communication between groups.

[s]I would also hope that it would normalize reminding others about their PPE. I was surprised to find how many faculty members in my department were incredibly uncomfortable with correcting the PPE or behavior of a student from a different lab. It meant effectively that we had extremely variable approaches to PPE and safety throughout our department.

[t]LOVE this idea. I’m guessing it makes the PI reflect on safety of each student as well as start a conversation about what’s going well and ways to improve

[u]We’ve seen dramatic improvement in safety issue resolution once we implemented this kind of program.

[v]Note how the word assist is used. Important to emphasize that the PI is delegating some of their duties to the LSO and throughout the lab but they are ultimately responsible for the safety of their researchers.

[w]Really important point. Too often I’ve seen an LSO designated just so the PI can essentially wash their hands of responsibility and just hand everything safety related to the LSO. It is also important for the PI to be prepared to back their LSO if another student doesn’t want to abide by a rule.

[x]Wondering what the risk is of institutions taking advantage of LSO programs by putting tasks on researchers that should really be the responsibility of the facility or EHS

[y]At UMN and UNC, do these tasks/roles contribute towards progress towards degree?

[z]In my experience at UNC serving as an LSO, it does not relate to progressing one’s studies/degree in any way (though there is the time commitment component of the role). At UMN, I know departmentally they have stronger support for their LSOs and requirements but I would not say that serving as an LSO helps/hinders degree progression (outside again of potential time commitments).

[aa]Thanks! I’m glad to hear that it doesn’t seem to hurt, but I think finding ways for it to help could make a huge difference. Thinking back to my own experience, my advisor counseled us to always have that end goal in mind when thinking about how we spent our time. This was in the context of not prioritizing TA duties ahead of research, but it is something that could argue against taking on these sorts of tasks.

[ab]Yeah, I think that is a really important point. If you’re PI continuously stresses only the results of research/imparts a sense of speed > safety; the students will pick up on that and shift in that direction through a function of their lab culture. So the flipside is if you can build and sustain a strong culture of safety; it becomes an inherent requirement, not an external check

[ac]It is important to keep in mind that this work should be considered in relation to other duties and to somehow be equally shared out among lab members. Depending on how this work is distributed, it can become an incredibly time-consuming set of tasks for one person to constantly be handling.

[ad]I have struggled with how to get buy-in for production of written SOPs.

[ae]It also increases the likelihood that the researchers will be able to implement the controls!

[af]Important point. It is often difficult in grad school to admit when you don’t understand or know how to do something. It is critical to make sure that they understand what is expected. I ran a small pilot project in which I found out that all 6 “soon to be defending” folks involved in the pilot had no clue what baffles in a hood were. Our Powerpoint “hoods” training was required every year. Ha!

[ag]In addition, it serves as a review process to catch risks hazards that the first writer may not have thought of. In industry this is a common practice that multiple people must check off on a protocol before it is used.

[ah]As outlined in this section, a good idea. We’re also working toward development of collaboration between staff with safety functions. For instance, have building managers from one department involved in inspections of buildings of other departments.

[ai]Also to avoid re-inventing the wheel. If another group has this expertise and has done risk assessments on the procedure you’re doing, better to start there rather than from scratch. You may even identify items for the other group to add.

[aj]Bottom up approach works extremely well when you have departmental support but not so much when the Head of the Dept doesn’t care.

[ak]They also can’t be effective if the concerns that the JST raise aren’t taken seriously by those who can change policies.

[al]An additional advantage is displaying value for performing safety duties. I.e. The culture is developed such that you work is appreciated rather than an annoyance

[am]I’m curious to hear what discoveries have been made about this.

[an]At UConn, we were trying to use surveys to essentially prove to our department leadership and faculty safety committee that graduate students actually DID want safety trainings – we just wanted them to be more specific to the things that we are actually concerned about it lab (as opposed to the same canned ones that they kept offering). My colleagues have told me that they are actually moving forward with these types of trainings now.

[ao]We also started holding quarterly LSO meetings because we proved to faculty through surveys that graduate students actually did want them (as long as they were designed usefully and addressed real issues in the research labs).

[ap]We work with representatives from various campus entities, which brings us a variety of insights. Yes focused training is much more valuable, and feels more worthwhile, educating both the trainer and trainee.

[aq]This is an impressive way for department administration to show endorsement and support for safety efforts.

[ar]Another way departments can communicate their commitment towards safety.

[as]We have one of these, too, but we need to move away from it. Not augmentation, but replacement. I don’t know what that looks like yet, but a content dump isn’t it.

[at]Agreed. At UNC we actually have an annual requirement to review the laboratory safety manual with our PI in some sort of setting (requires the PI to sign off on some forms saying they did it). Obviously with the length, that isn’t feasible in its entirety; so we’d highlight a few key sections but yeah. Not the most useful document

[au]I see the CHP or lab safety manual as education/resources and the training as actually practicing behaviors that are expected of researchers, which is critical to actually enforcing policies

[av]Agreed. I always felt any “training” should actually be doing something hands-on. Sitting in a lecture hall watching a Powerpoint should not qualify as “training.”

[aw]Agreed as well Jessica. That is why now all our safety trainings are hands on as you stated. It has worked and come across MUCH better. Even with our facilities and security personnel.

[ax]I really like how continued training is embedded throughout regular day-to-day activities in many cases, this is important. I would add that it is important to have the beginning training available for refresher or reference as needed but don’t think it’s worth it to completely retake the online trainings.

[ay]Let me remind everyone that when a senior lab person shows a junior person how to do a procedure, training is occurring. Including safety aspects in the teaching is critical. Capturing this with a note in the junior person’s lab notebook documents it. The UCLA prosecution would not have occurred if the PD had done this with Ms. Sangji.

[az]I’m very curious to hear about examples of this.

[ba]Wow. Getting the PIs to do this would be awesome. I wonder what is the PI incentive. Part of their annual review?

[bb]Agreed, this seems like a big ask

[bc]In recognition of this our department has put together an on-line lab research mentoring guide and we’re looking for ways to disseminate info about it.

[bd]This works both ways; a mentee ending up with a mentor who doesn’t emphasize safety in their work might be communicating that to their mentees as well.

[be]This has been something I’ve been concerned about and am not sure how to address as an embedded safety professional.

[bf]Just a thought – It seems like there is a big overlap between continued training and developing awareness, which makes sense

[bg]In working with graduate students, I have found a really odd understanding of this to be quite common. Many think that they are only responsible for understanding what is going on in their own labs – and not for what may be going on next door.

[bh]So true. This is where EHS could really help departments or buildings define safety better. Most people may not be aware that the floor above them uses pyrophorics, etc.

[bi]I think this speaks to how insular grad school almost forces you to be. You spend so much time deepening your knowledge and understanding of your area of research that you have no time to develop breadth.

[bj]Yeah, these are great points. Anecdotally, at UNC when we started the JST we really struggled to get any engagement whatsoever out of the computational groups, even when their work space is across the hall from heavily synthetic organic chemistry groups. We didn’t really solve this, but I know it was and is something we’re chewing on

[bk]Not mentioned explicitly in this section, but documenting what is learned is critically important. As noted earlier in the paper, students cycle through labs. The knowledge needs to stay there.

[bl]From my perspective, awareness seems to be directly tied t the PIs priorities except for the 1 in 20 student.

[bm]It seems like something like this happened in the 2010 Texas Tech explosion.

[bn]This highlights the importance of developing procedures/protocols/SOPs, secondary review, and good training/onboarding practicing for specific techniques

[bo]These are always great discussions and fruitful.

[bp]Agreed. Even if you never encounter that scenario in your career, the process of how to think about responding to the unexpected is a generalizable skill.

[bq]I also think it is important to use something like this to help researchers think about how to respond to incidents when they do happen in order to decrease the harm caused by the incident.

[br]This is really great. I think a big part of knowing what to do when a lab incident occurs has a lot to do with thinking about how to respond to the incident before it happens.

[bs]I’m really glad this is included in here. Most of risk assessment is actually very intuitive but this highlights the importance of going through the process in a formal way. But the term is so unfamiliar to researchers sometimes that it seems unapproachable

[bt]I’m interested in learning how others judge the way to find this balance.

[bu]These are useful if the student doing the work develops the checklist otherwise it becomes just a checklist without understanding and thought. I see many students look at these checklist and ignore hazards because it is not on or part of the list.

[bv]Good point. It would likely be a good practice to periodically update these as well – especially encouraging folks to bring in things that they’ve come across that were done poorly or they had to clean up.

[bw]These are great points. The checklists we’ve designed try their best to highlight major hazards, but due to brevity it isn’t possible to cover everything. I think as Jessica pointed out, is that if they are reviewed periodically, that can be a huge boost in a way that reviewing and updating SOPs as living documents is also important

[bx]This is important – a good checklist is neither an SOP nor a training.

[by]I utilize checklists but sometimes see a form of checklist fatigue – a repeated user thinks they know it and doesn’t bother with the checklist.

So the comment about a GOOD checklist is applicable.

[bz]I’m impressed with the ideas and diversity and discussion of alternatives. It’s inspiring. However, I’m trying to institute a culture of safety where I am and many of these ideas aren’t possible for me. I’m in chemistry at a 2-year (community) college, and I don’t have TAs, graduate students, etc. We’re not a research institution which is somewhat of an advantage because our situations are relatively static and theoretically controllable . My other problem is I’m trying to carry the safety culture across the college and to our sister colleges, to departments like maintenance and operations, art, aircraft mechanics, welding etc.

I would love to see ways to address

1. just a teaching college

2. other processes across campus.

I head a safety committee but am challenged to keep people engaged and aware.

[ca]I’ve found some helpful insights from others about this sort of thing from NAOSMM. They have a listserv and annual conferences where they offer workshops and presentations on safety helpful for non-research institutions like to what you’re describing.

Positive Feedback for Improved Safety Inspections

Melinda Box, MEd, presenter

Ciana Paye, &

Maria Gallardo-Williams, PhD

North Carolina State University

Melinda’s powerpoint can be downloaded from here.

03/17 Table Read for The Art & State of Safety Journal Club

Excerpts from “Positive Feedback via Descriptive Comments for Improved Safety Inspection Responsiveness and Compliance”

The full paper can be found here: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.chas.1c00009

Safety is at the core of industrial and academic laboratory operations worldwide and is arguably one of the most important parts of any enterprise since worker protection is key to maintaining on-going activity.28 At the core of these efforts is the establishment of clear expectations regarding acceptable conditions and procedures necessary to ensure protection from accidents and unwanted exposures[a]. To achieve adherence to these expectations, frequent and well-documented inspections are made an integral part of these systems.23

Consideration of the inspection format is essential to the success of this process.31 Important components to be mindful about include frequency of inspections, inspector training, degree of recipient involvement, and means of documentation[b][c][d][e] . Within documentation, the form used for inspection, the report generated, and the means of communicating, compiling, and tracking results all deserve scrutiny in order to optimize inspection benefits.27

Within that realm of documentation, inspection practice often depends on the use of checklists, a widespread and standard approach. Because checklists make content readily accessible and organize knowledge in a way that facilitates systematic evaluation, they are understandably preferred for this application. In addition, checklists reduce frequency of omission errors and, while not eliminating variability, do increase consistency in inspection elements[f][g][h][i][j] among evaluators because users are directed to focus on a single item at a time.26 This not only amplifies the reliability of results, but it also can proactively communicate expectations to inspection recipients and thereby facilitate their compliance preceding an inspection.

However, checklists do have limitations. Most notably, if items on a list cover a large scale and inspection time is limited, reproducibility in recorded findings can be reduced[k]. In addition, individual interpretation and inspector training and preparation can affect inspection results[l][m][n][o][p][q].11 The unfortunate consequence of this variation in thoroughness is that without a note of deficiency there is not an unequivocal indication that an inspection has been done. Instead, if something is recorded as satisfactory, the question remains whether the check was sufficiently thorough or even done at all. Therefore, in effect, the certainty of what a checklist conveys becomes only negative feedback[r][s][t].

Even with uniformity of user attention and approach, checklists risk producing a counterproductive form of tunnel vision[u] because they can tend to discourage recognition of problematic interactions and interdependencies that may also contribute to unsafe conditions.15 Also, depending on format, a checklist may not provide the information on how to remedy issues nor the ability[v][w] to prioritize among issues in doing follow-up.3 What’s more, within an inspection system, incentive to pursue remedy may only be the anticipation of the next inspection, so self-regulating compliance in between inspections may not be facilitated.[x][y][z][aa][ab][ac]22

Recognition of these limitations necessitates reconsideration of the checklist-only approach, and as part of that reevaluation, it is important to begin with a good foundation. The first step, therefore, is to establish the goal of the process. This ensures that the tool is designed to fulfill a purpose that is widely understood and accepted.9 Examples of goals of an environmental health and safety inspection might be to improve safety of surroundings, to increase compliance with institutional requirements, to strengthen preparedness for external inspections, and/or to increase workers’ awareness and understanding of rules and regulations. In all of these examples, the aim is to either prompt change or strengthen existing favorable conditions. While checklists provide some guidance for change, they do not bring about that change, [ad][ae]and they are arguably very limited when it comes to definitively conveying what favorable conditions to strengthen. The inclusion of positive feedback fulfills these particular goals.

A degree of skepticism and reluctance to actively include a record of positive observations[af][ag] in an inspection, is understandable since negative feedback can more readily influence recipients toward adherence to standards and regulations. Characterized by correction and an implicit call to remedy, it leverages the strong emotional impact of deficiency to encourage limited deviation from what has been done before.19 However, arousal of strong negative emotions, such as discouragement, shame, and disappointment, also neurologically inhibits access to existing neural circuits thereby invoking cognitive, emotional, and perceptual impairment.[ah][ai][aj]10, 24, 25 In effect, this means that negative feedback can also reduce the comprehension of content and thus possibly run counter to the desired goal of bringing about follow up and change.2

This skepticism and reluctance may understandably extend to even including positive feedback with negative feedback since affirmative statements do not leave as strong of an impression as critical ones. However, studies have shown that the details of negative comment will not be retained without sufficient accompanying positive comment.[ak][al][am][an][ao][ap][aq]1[ar][as] The importance of this balance has also been shown for workplace team performance.19 The correlation observed between higher team performance and a higher ratio of positive comments in the study by Losada and Heaphy is attributed to an expansive emotional space, opening possibilities for action and creativity. By contrast, lower performing teams demonstrated restrictive emotional spaces as reflected in a low ratio of positive comments. These spaces were characterized by a lack of mutual support and enthusiasm, as well as an atmosphere of distrust and [at]cynicism.18

The consequence of positive feedback in and of itself also provides compelling reason to regularly and actively provide it. Beyond increasing comprehension of corrections by offsetting critical feedback, affirmative assessment facilitates change by broadening the array of solutions considered by recipients of the feedback.13 This dynamic occurs because positive feedback adds to an employees’ security and thus amplifies their confidence to build on their existing strengths, thus empowering them to perform at a higher level[au].7

Principles of management point out that to achieve high performance employees need to have tangible examples of right actions to take[av][aw][ax][ay][az], including knowing what current actions to continue doing.14, 21 A significant example of this is the way that Dallas Cowboys football coach, Tom Landry, turned his new team around. He put together highlight reels for each player that featured their successes. That way they could identify within those clips what they were doing right and focus their efforts on strengthening that. He recognized that it was not obvious to natural athletes how they achieved high performance, and the same can be true for employees and inspection recipients.7

In addition, behavioral science studies have demonstrated that affirmation builds trust and rapport between the giver and the receive[ba]r[bb][bc][bd][be][bf][bg].6 In the context of an evaluation, this added psychological security contributes to employees revealing more about their workplace which can be an essential component of a thorough and successful inspection.27 Therefore, positive feedback encourages the dialogue needed for conveying adaptive prioritization and practical means of remedy, both of which are often requisite to solving critical safety issues.[bh]

Giving positive feedback also often affirms an individual’s sense of identity in terms of their meaningful contributions and personal efforts. Acknowledging those qualities, therefore, can amplify them. This connection to personal value can evoke the highest levels of excitement and enthusiasm in a worker, and, in turn, generate an eagerness to perform and fuel energy to take action.8

Looked at from another perspective, safety inspections can feel personal. Many lab workers spend a significant amount of time in the lab, and as a result, they may experience inspection reports of that setting as a reflection on their performance rather than strictly an objective statement of observable work. Consideration of this affective impact of inspection results is important since, when it comes to learning, attitudes can influence the cognitive process.29 Indeed, this consideration can be pivotal in transforming a teachable moment into an occasion of learning.4

To elaborate, positive feedback can influence the affective experience in a way that can shift recipients’ receptiveness to correction[bi][bj]. Notice of inspection deficiencies can trigger a sense of vulnerability, need, doubt, and/or uncertainty. At the same time, though, positive feedback can promote a sense of confidence and assurance that is valuable for active construction of new understanding. Therefore, positive feedback can encourage the transformation of the intense interest that results from correction into the contextualized comprehension necessary for successful follow-up to recorded deficiencies.

Overall, then, a balance of both positive and negative feedback is crucial to ensuring adherence to regulations and encouraging achievement.[bk]2, 12 Since positive emotion can influence how individuals respond to and take action from feedback, the way that feedback is formatted and delivered can determine whether or not it is effective.20 Hence, rooting an organization in the value of positivity can reap some noteworthy benefits including higher employee performance, increased creativity, and an eagerness in employees to engage.6

To gain these benefits, it is, therefore, necessary to expand from the approach of the checklist alone.16 Principles of evaluation recommend a report that includes both judgmental and descriptive information. This will provide recipients with the information they seek regarding how well they did and the successfulness of their particular efforts.27 Putting the two together creates a more powerful tool for influence and for catalyzing transformation.

In this paper the authors would like to propose an alternative way to format safety inspection information, in particular, to provide feedback that goes beyond the checklist-only approach. The authors’ submission of this approach stems from their experiences of implementing a practice of documenting positive inspection findings within a large academic department. They would like to establish, based on educational and organizational management principles, that this practice played an essential role in the successful outcome of the inspection process in terms of corrections of safety violations, extended compliance, and user satisfaction. [bl][bm][bn][bo]

[a]There is also a legal responsibility of the purchaser of a hazardous chemical (usually the institution, at a researcher’s request) to assure it is used in a safe and healthy manner for a wide variety of stakeholders

[b]I would add what topics will be covered by the inspection to this list. The inspection programs I was involved in/led had a lot of trouble deciding whether the inspections we conducted were for the benefit of the labs, the institution or the regulatory authorities. Each of these stakeholders had a different set of issues they wanted to have oversight over. And the EHS staff had limited time and expertise to address the issues adequately from each of those perspectives.

[c]This is interesting to think about. As LSTs have taken on peer-to-peer inspections, they have been using them as an educational tool for graduate students. I would imagine that, even with the same checklist, what would be emphasized by an LST team versus EHS would end up being quite a bit different as influenced by what each group considered to be the purpose of the inspection activity.

[d]Hmm, well maybe the issue is trying to cram the interests and perspectives of so many different stakeholders into a single, annual, time-limited event 😛

[e]I haven’t really thought critically about who the stakeholders are of an inspection and who they serve. I agree with your point Jessica, that the EHS and LST inspections would be different and focus on different aspects. I feel include to ask my DEHS rep for his inspection check list and compare it to ours.

[f]This is an aspirational goal for checklists, but is not often well met. This is because laboratories vary so much in the way they use chemicals that a one size checklist does not fit all. This is another reason that the narrative approach suggested by this article is so appealing

[g]We have drafted hazard specific walkthrough rubrics that help address that issue but a lot of effort went into drafting them and you need someone with expertise in that hazard area to properly address them.

[h]Well I do think that, even with the issues that you’ve described, checklists still work towards decreasing variability.

In essence, I think of checklists as directing the conversation and providing a list of things to make sure that you check for (if relevant). Without such a document, the free-form structure WOULD result in more variability and missed topics.

Which is really to say that, I think a hybrid approach would be the best!

[i]I agree that a hybrid approach is ideal, if staff resources permit. The challenge is that EHS staff are responding to a wide variety of lab science issues and have a hard time being confident that they are qualified to raise issues. Moving from major research institutions to a PUI, I finally feel like I have the time to provide support to not only raise concerns but help address them. At Keene State, we do modern science, but not exotic science.

[j]I feel like in the end, it always comes down to “we just don’t have the resources…”

Can we talk about that for a second? HOW DO WE GET MORE RESOURCES FOR EHS : /

[k]I feel like that would also be the case for a “descriptive comment” inspection if the time is limited. Is there a way that the descriptive method could improve efficiency while still covering all inspection items?

[l]This is something my university struggles with in terms of a checklist. There’s quite a bit of variability between inspections in our labs done by different inspectors. Some inspectors will catch things that others would overlook. Our labs are vastly different but we are all given the same checklist – Our checklist is also extensive and the language used is quite confusing.

[m]I have also seen labs with poor safety habits use this to their advantage as well. I’ve known some people who strategically put a small problem front and center so that they can be criticized for that. Then the inspector feels like they have “done their job” and they don’t go looking for more and miss the much bigger problem(s) just out of sight.

[n]^ That just feels so insidious. I think the idea of the inspector looking for just anything to jot down to show they were looking is not great (and something I’ve run into), but you want it to be because they CANT find anything big, not just to hide it.

[o]Amanda, our JST has had seminars to help prepare inspectors and show them what to look for. We also include descriptions of what each inspection score should look like to help improve reproducibility.

[p]We had experience with this issue when we were doing our LSTs Peer Lab Walkthrough! For this event, we have volunteer graduate students serve as judges to walk through volunteering labs to score a rubric. One of the biggest things we’ve had to overhaul over the years is how to train and prepare our volunteers.

So far, we’ve landed on providing training, practice sessions, and using a TEAM of inspectors per lab (rather than just one). These things have definitely made a huge difference, but it’s also really far from addressing the issue (and this is WITH a checklist)

[q]I’d really like to go back to peer-peer walkthroughs and implement some of these ideas. Unfortunately, I don’t think we are there yet in terms of the pandemic for our university and our grad students being okay with this. Brady, did you mean you train the EHS inspectors or for JST walkthroughs? I’ve given advice about seeing some labs that have gone through inspections but a lot of items that were red flags to me (and to the grad students who ended up not pointing it out) were missed / not recorded.

[r]This was really interesting to read, because when I was working with my student safety team to create and design a Peer Lab Walkthrough, this was something we tried hard to get around even though we didn’t name the issue directly.

We ended up making a rubric (which seems like a form of checklist) to guide the walkthrough and create some uniformity in responding, but we decided to make it be scored 1-5 with a score of *3* representing sufficiency. In this way, the rubric would both include negative AND positive feedback that would go towards their score in the competition.

[s]I think the other thing that is cool about the idea of a rubric, is there might be space for comments, but by already putting everything on a scale, it can give an indication that things are great/just fine without extensive writing!

[t]We also use a rubric but require a photo or description for scores above sufficient to further highlight exemplary safety.

[u]I very much saw this in my graduate school lab when EHS inspections were done. It was an odd experience for me because it made me feel like all of the things I was worried about were normal and not coming up on the radar for EHS inspections.

[v]I think this type of feedback would be really beneficial. From my experience (and hearing others), we do not get any feedback on how to fix issues. You can ask for help to fix the issues, but sometimes the recommendations don’t align with the labs needs / why it is an issue in the first place

[w]This was a major problem in my 1st research lab with the USDA. We had safety professionals who showed up once per year for our annual inspection (they were housed elsewhere). I was told that a set up we had wasn’t acceptable. I explained why we had things set up the way we did, then asked for advice on how to address the safety issues raised. The inspector literally shrugged his shoulders and gruffly said to me “that’s your problem to fix.” So – it didn’t get fixed. My PI had warned my about this attitude (so this wasn’t a one-off), but I was so sure that if we just had a reasonable, respectful conversation….

[x]I think this is a really key point. We had announced inspections and were aware of what was on the checklists. As a LSO, we would in the week leading up to it get the lab in tip-top shape. Fortunately, we didn’t always have a ton of stuff to fix in the week leading up to the inspection, but its easy to imagine reducing things to a yes/no checklists can mask long-term problems that are common in-between inspections

[y]My lab is similar to this. When I first joined and went through my first inspection – the week prior was awful trying to correct everything. I started implementing “clean-ups” every quarter because my lab would just go back to how it was after the inspection.

[z]Same

[aa]Our EHS was short-staffed and ended up doing “annual inspections” 3 years apart – once was before I joined my lab, and the next was ~1.5 years in. The pictures of the incorrect things found turned out to be identical to the inspection report from 3 years prior. Not just the same issues, but quite literally the same bottles/equipment.

[ab]Yeah, we had biannual lab cleanups that were all day events, and typically took place a couple months before our inspections; definitely helped us keep things clean.

One other big things is when we swapped to subpart K waste handling (cant keep longer than 12months), we just started disposing of all waste every six months so that way nothing could slip through the cracks before an inspection

[ac]Jessica, you’re talking about me and I don’t like it XD

[ad]I came to feel that checklists were for things that could be reviewed when noone was in the room and that narrative comments would summarize conversations about inspectors’ observations. These are usually two very different sets of topics.

[ae]We considered doing inspections “off-hours” to focus on the checklist items, until we realized there was no such thing as off hours in most academic labs. Yale EHS found many more EHS problems during 3rd shift inspections than daytime inspections

[af]This also feels like it would be a great teachable moment for those newer to the lab environment. We often think that if no one said anything, I guess it is okay even if we do not understand why it is okay. Elucidating that something is being done right “and this is why” is really helpful to both teach and reinforce good habits.

[ag]I think that relates well to the football example of highlighting the good practices to ensure they are recognized by the player or researcher.

[ah]I noticed that not much was said about complacency, which I think can both be a consequence of an overwhelm of negative feedback and also an issue in and of itself stemming from culture. And I think positive feedback and encouragement could combat both of these contributors to complacency!

[ai]Good point. It could also undermine the positive things that the lab was doing because they didn’t actually realize that the thing they were previously doing was actually positive. So complacency can lead to the loss of things that you were doing right before.

[aj]I have seen situations where labs were forced to abandon positive safety efforts because they were not aligned with institutional or legal expectations. Compliance risk was lowered, but physical risk increased.

[ak]The inclusion of both positive and negative comments shows that the inspector is being more thorough which to me would give it more credibility and lead to greater acceptance and retention of the feedback.

[al]I think they might be describing this phenomenon a few paragraphs down when they talk about trust between the giver and receiver.

[am]This is an interesting perspective. I have found that many PIs don’t show much respect for safety professionals when they deliver bad news. Perhaps the delivery of good news would help to reinforce the authority and knowledge base of the safety professionals – so that when they do have criticism to deliver, it will be taken more seriously.

[an]The ACS Pubs advice to reviewers of manuscripts is to describe the strengths of the paper before raising concerns. As an reviewer, I have found that approach very helpful because it makes me look for the good parts of the article before looking for flaw.

[ao]The request for corrective action should go along with a discussion with the PI of why change is needed and practical ways it might be accomplished.

[ap]I worked in a lab that had serious safety issues when I joined. Wondering if the positive -negative feedback balance could have made a difference in changing the attitudes of the students and the PI.

[aq]It works well with PIs with an open mind; but some PIs have a sad history around EHS that has burnt them out on trying to work with EHS staff. This is particularly true if the EHS staff has a lot of turnover.

[ar]Sandwich format- two positives (bread) between the negative (filling).

[as]That crossed my mind right away as well.

[at]I wonder how this can contribute to a negative environment about lab-EHS interactions? If there is only negative commentary (or the perception of that) flowing in one direction, would seem that it would have an impact on that relationship

[au]I see how providing positive feedback along with the negative feedback could help do away with the feeling the inspector is just out to get you. Instead, they are here to provide help and support.

[av]This makes me consider how many “problem” examples I use in the safety training curriculum.

[aw]This is a good point. From a learning perspective, I think it would be incredibly helpful to see examples of things being done right – especially when what is being shown is a challenge and is in support of research being conducted.

[ax]I third this so hard! It was also something that I would seek out a lot when I was new but had trouble finding resources on. I saw a lot of bad examples—in training videos, in the environments around me—but I was definitely starved for a GOOD example to mimic.

[ay]I read just part of the full paper. It includes examples of positive feedback and an email that was sent. The example helped me get the flavor of what the authors were doing.

[az]This makes a lot of sense to me – especially from a “new lab employee” perspective.

[ba]Referenced in my comment a few paragraphs above.

[bb]I suspect that another factor in trust is the amount of time spent in a common environment. Inspectors don’t have a lot of credibility if they are only visit a place annually where a lab worker spends every day.

[bc]A lot of us do not know or recognize our inspectors by name or face (we’ve also had so much turn around in EHS personnel and don’t even have a CHO). I honestly would not be able to tell you who does inspections if not for being on our universities LST. This has occurred in our lab (issue of trust) during a review of an inspection of our radiation safety inspection. The waste was not tested properly, so we were questioned on our rad waste. It was later found that the inspector unfortunately didn’t perform the correct test for testing the pH. My PI did not take it very well after having to correct them about this.

[bd]I have run into similar issues when inspectors and PIs do not take the time to have a conversation, but connect only by e-mail. Many campuses have inspection tracking apps which make this too easy a temptation for both sides

[be]Not only a conversation but inspectors can be actively involved in improving conditions- eg supply signs, ppe, similar sop’s…

[bf]Yes, sometimes, it’s amazing how little money it can take to show a good faith effort from EHS to support their recommendations. Other times, if it is a capital cost issue, EHS is helpless to assist even if there is a immediate concern.

[bg]I have found inspections where the EHS openly discuss issues and observations as they are making the inspection very useful Gives me the chance to ask the million questions I have about safety in the lab.

[bh]We see this in our JST walkthroughs. We require photos or descriptions of above acceptable scores and have some open ended discussion questions at the end to highlight those exemplary safety protocols and to address areas that might have been lacking.

[bi]Through talking with other students reps, we usually never know what we are doing “right” during the inspections. I think this would benefit in a way that shared positive feedback, would then help the other labs that might have been marked on their inspection checklist for that same item and allow them a resource on how to correct issues.

[bj]I think this is an especially important point in an educational environment. Graduate students are there to learn many things, such as how to maintain a lab. It is weird to be treated as if we should already know – and get no feedback about what is being done right and why it is right. I often felt like I was just sort of guessing at things.

[bk]At UVM, we hosted an annual party where we reviewed the most successful lab inspections. This was reasonably well received, particularly by lab staff who were permanent and wanted to know how others in the department were doing on the safety front

[bl]This can be successful, UNTIL a regulatory inspection happens that finds significant legal concerns related primarily to paperwork issues. Then upper management is likely to say “enough of the nice guy approach – we need to stop the citations.” Been there, done that.

[bm]Fundamentally, I think there needs to be two different offices. One to protect the people, and one to protect the institution *huff huff*

[bn]When that occurs, there is a very large amount of friction between those offices. And the Provost ends up being the referee. That is why sometimes there is no follow up to an inspection report that sounds dire.

[bo]But I feel like there is ALREADY friction between these two issues. They’re just not as tangible and don’t get as much attention as they would if you have two offices directly conflicting.

These things WILL conflict sometimes, and I feel like we need a champion for both sides. It’s like having a union. Right now, the institution is the only one with a real hand in the game, so right now that perspective is the one that will always win out. It needs more balance.

CHAS presentations from the Spring 2022 national meeting

Below are PDF versions of presentations from CHAS symposia and those in other divisions from the Spring, 2022 meeting.

Value of storytelling to build empathy, awareness, and inclusivity in EHS, Dr. Kali Miller

Inclusive risk assessment: Why and how? Ralph Stuart, CIH, CCHO

Some thoughts about how to safely accommodate people with disabilities in the laboratory, Debbie Decker, CCHO

Job design for the “hidden” disabled professional, Dr. Daniel R. Kuespert, CSP

Discussion of accommodation and advocacy for graduate student researchers, Catherine Wilhelm

Parsing Chemical Safety Information Sources, Ralph Stuart, CIH, CCHO

“Safe fieldwork strategies for at-risk individuals, their supervisors and institutions” and “Trauma and Design”

CHAS Journal Club Nov 10, 2021

On November 10, the CHAS Journal Club discussed two articles related to social safety considerations in research environments. The discussion was lead by Anthony Appleton, of Colorado State University. Anthony’s slides are below and the comments from the table read of the two articles can be found after that.

Table Read for The Art & State of Safety Journal Club

Excerpts from “Safe fieldwork strategies for at-risk individuals, their supervisors and institutions” and “Trauma and Design”

Full articles can be found here:

Safe fieldwork strategies: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-020-01328-5.pdf

Trauma and Design: https://medium.com/surviving-ideo/trauma-and-design-62838cc14e94

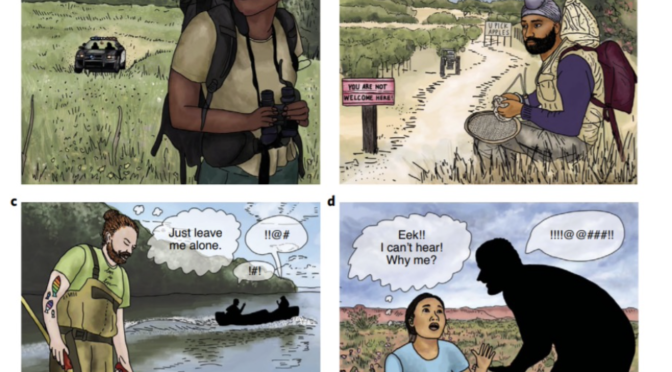

Safe fieldwork strategies for at-risk individuals, their supervisors and institutions

Everyone deserves to conduct fieldwork[a] as safely as possible; yet not all fieldworkers face the same risks going into the field. At-risk individuals include minority identities of the following: race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, gender identity and/or religion. When individuals from these backgrounds enter unfamiliar communities in the course of fieldwork[b][c][d], they may be placed in an uncomfortable and potentially unsafe ‘othered’ position, and prejudice may manifest against them. Both immediately and over the long term, prejudice-driven conflict can threaten a researcher’s physical health and safety[e], up to and including their life. Additionally, such situations impact mental health, productivity and professional development.

The risk to a diverse scientific community

Given the value of a diverse scientific community[f], the increased risk to certain populations in the field — and the actions needed to protect such individuals — must be addressed by the entire scientific community if we are to build and retain diversity in disciplines that require fieldwork. While many field-based disciplines are aware of the lack of diversity in their cohorts, there may be less awareness of the fact that the career advancement of minoritized researchers can be stunted or permanently derailed[g] after a negative experience during fieldwork.

Defining and assessing risk

Fieldwork in certain geographic areas and/or working alone has led many researchers to feel uncomfortable, frightened and/or threatened by local community members and/or their scientific colleagues. Local community members may use individuals’ identities as a

biased marker of danger to the community, putting them at risk from law enforcement and vigilante behaviours. Researchers’ feelings of discomfort in the field have been reaffirmed by the murders of Black, Indigenous and people of colour including Emmett Till, Tamir Rice, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor; however, fieldwork also presents increased risk for individuals in other demographics. For example, researchers who wear clothing denoting a minority religion or those whose gender identity, disability and/or sexual orientation are made visible can be at increased risk when conducting fieldwork. Several studies have documented the high incidence of harassment or misconduct that occurs in the field. Based on lived experience, many at-risk individuals already consider how they will handle harassment or misconduct before they ever get into the field, but this is a burden that must be shared[h][i] by their lab, departments and institutions[j] as well. Labs, departments and institutions must address such risks by informing future fieldworkers of potential risks and discussing these with them, as well as making available resources and protocols for filing complaints and accessing[k][l][m] training well before the risk presents itself.

Conversations aimed at discussing potential risks rarely occur between researchers and their supervisors, especially in situations where supervisors may not be aware of the risk posed[n] or understand the considerable impact[o] of these threats on the researcher, their productivity and their professional development. Quoted from Barker[p][q]: “…faculty members of majority groups (such as White faculty in predominantly White institutions (PWI)) may not have an understanding of the ‘educational and non-academic experiences’ of ethnic minority graduate students or lack ‘experience in working in diverse contexts’.” This extends to any supervisor who does not share identity(ies) with those whom they supervise, and would have had to receive specific training on this subject matter in order to be aware of these potential risks.

Dispatches from the field

The following are examples of situations that at-risk researchers have experienced in the field: police have been called on them; a gun has been pulled on them[r][s][t][u] (by law enforcement and/or local community members); hate symbols have been displayed at or near the field site; the field site is an area with a history of hate crimes against their identity (including ‘sundown towns’, in which all-white communities physically, or through threats of extreme violence, forced people of colour out of town by sundown); available housing has historically problematic connotations (for example, a former plantation where people were enslaved); service has been refused (for example, food or housing); slurs have been used or researchers verbally abused due to misunderstandings about a disability; undue monitoring or stalking by unknown and potentially aggressive individuals; sexual harassment and/or assault occurred. Such traumatic situations are a routine expectation in the lives of at-risk researchers. The chance of these scenarios arising is exacerbated in field settings where researchers are alone[v][w], in an unfamiliar area with little-to-no institutional or peer support, or are with research team members who may be uninformed, unaware or not trusted. In these situations, many at-risk researchers actively modify their behaviour in an attempt to avoid the kinds of situations described above. However, doing so is mentally draining, with clear downstream effects on their ability to conduct research.[x][y][z]

Mitigating risk[aa][ab][ac]

The isolating and severe burden of fieldwork risks to minoritized individuals means that supervisors[ad] bear a responsibility to educate themselves[ae] on the differential risks posed to their students and junior colleagues in the field. When learning of risks and the realized potential for negative experiences in the field, the supervisor should work with at-risk researchers to develop strategies and practices for mitigation in ongoing and future research environments.[af] Designing best practices for safety in the field for at-risk researchers will inform all team members and supervisors of ways to promote safe research, maximize productivity and engender a more inclusive culture in their community. This means asking[ag][ah][ai][aj][ak][al][am] who is at heightened risk, including but not limited to those expressing visible signs of their race/ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression (for example, femme-identifying, transgender, non-binary) and/or religion (for example, Jewish, Muslim and Sikh[an][ao]). Importantly, the condition of being ‘at-risk’ is fluid with respect to fieldwork and extends to any identity that is viewed as different[ap] from the local community in which the research is being conducted. In some cases, fieldwork presents a situation where a majority identity at their home institution can be the minority identity at the field site, whether nearby or international. Supervisors, colleagues and students must also interrogate where and when risk is likely to occur: an individual could be at-risk whenever someone perceives them as different in the location where they conduct research. Given the variety of places that at-risk situations can occur, both at home, in country or abroad, researchers and supervisors must work under the expectation that prejudice can arise in any situation.[aq]

Strategies for researchers, supervisors, and institutions to minimize risk

Here we provide a list of actions to minimize risk and dange[ar][as]r while in the field compiled from researchers, supervisors and institutional authorities from numerous affiliations. These strategies are used to augment basic safety best practices. Furthermore, the actions can be used in concert with each other and are flexible with regards to the field site and the risk level to the researcher. These strategies are not comprehensive; rather, they can be tailored to a researcher’s situation.

We acknowledge that it is an unfair burden that at-risk populations[at] must take additional precautions to protect themselves. We therefore encourage supervisors, departments and institutions to collectively work to minimize these harms by: (1) meeting with all trainees to discuss these guidelines, and maintaining the accessibility of these guidelines (Box 1) and additional resources (Table 1); (2) fostering a department-wide discussion on

safety during fieldwork for all researchers; (3) urging supervisors to create and integrate contextualized safety guidelines for researchers in lab, departmental and institutional resources.

A hold harmless recommendation for all

Topics related to identity are inherently difficult to broach, and may involve serious legal components. For example, many supervisors have been trained to avoid references to a researcher’s identity and to ensure that all researchers they supervise are treated equally regardless of their identities.[au] Many institutions codify this practice in ways that conflict with the goals outlined in the previous sentence, as engaging in dialogue with at-risk individuals is viewed as a form of targeting or negative bias. In a perfect world, all individuals would be aware of these risks and take appropriate actions to mitigate them and support individuals at heightened risk. In reality, these topics will likely often arise just as an at-risk individual is preparing to engage in fieldwork, or even during the course of fieldwork. We therefore strongly encourage all relevant individuals and institutions to ‘hold harmless’ any good-faith effort to use this document as a framework for engaging in

a dialogue about these core issues of safety and inclusion. Specifically, we recommend that it should never be considered a form of bias or discrimination for a supervisor to offer a discussion on these topics to any individual that they supervise[av][aw][ax][ay]. The researcher or supervisee receiving that offer should have the full discretion and agency to pursue it further, or not. Simply sharing this document [az]is one potential means to make such an offer in a supportive and non-coercive way, and aligns with the goals we have outlined towards making fieldwork safe, equitable and fruitful for all.

Trauma and Design

1. Validating your experience. It’s important to know that workplace trauma can be destabilizing, demoralizing, and dehumanizing. And when it happens in a design-centric organization where there are sometimes shallowly professed[ba] values of human-centeredness, empathy, and the myth of bringing your full, authentic self to work, it can leave you spinning in a dizzying state of cognitive dissonance and moral injury.

A common side effect of workplace abuse is invalidation, which is defined as “the rejection or dismissal of your thoughts, feelings, emotions, and behaviors as being valid

and understandable.” Invalidation can cause significant damage or upset to your psychological health and well-being. What’s worse, the ripple effects of these layers of dismissal are traumatic, often happen in isolation, and may lead to passive or more overt forms of workplace and institutional betrayal. If this is (or has been) your experience, it’s important to know that (1) you are not alone and (2) your experience is valid and real.[bb]

2. Seeking safety. Workplace-induced emotional trauma is very real and, unfortunately, on the rise. The research is also clear: continuous exposure to trauma can hurt our bodies and lead to debilitating levels of burnout, anxiety, depression, traumatic stress, and a host of other health issues. Episodic and patterned experiences like micro- and macro-aggressions, bullying, gaslighting, betrayal, manipulation, and other forms of organizational abuse can have both immediate and lasting psychological and physiological effects. So, what can we do?[bc]

• To go to HR and management or not? There is a natural inclination to document and

report workplace abuse and to then work within the HR structures that are in place where we work. But many profit- and productivity-driven workplaces are remarkably inept at putting employees (the primary human resource) first[bd][be][bf][bg]. The nauseating effects of this can lead to deeply entrenched incompetent or avoidant behaviors by the very people who we expect to listen to and support us (read: HR). Even with this said, there is value in documenting events as they occur so that you can remember the details and not forget the context later. You may also have a situation so egregious or blatantly illegal that documentation will be necessary.

• Do you need accommodations? Employees need to be cared for in ways that our leaders don’t always recognize, nor value. Workplace trauma, as well as current and past trauma, can get exacerbated resulting in impairing symptoms or a legally protected disability accommodation. Sometimes seeking out accommodations as part of the process can hold your immediate supervisor accountable (as well as their respective leadership chain) to meet your needs. The Job Accommodation Network (JAN) is a source of free, expert, and confidential guidance on job accommodations and disability employment issues. JAN provides free one-on-one practical guidance and technical assistance on job accommodation solutions.